For hundreds of years, the shifting shingle within it’s bay has caused problems for the town of Seaford. Even today we try to tame this movement with a convoy of massive bulldozers which try to put the beach in its place. The Ouse once entered the sea in Seaford Bay but the shingle constantly blocked the outfall making it difficult for Seaford’s fishing fleet to operate and also shipping visiting Lewes which once had a small ship-building industry.

Several Royal Commissions sought to remedy these problems by suggesting break-waters and piers but none were built. In 1537 plans were announced to cut a channel to the sea near the village of Meeching, and by 1539 a “newe-haven” was mentioned. The fishermen of the old Cinque Port probably continued to use Seaford harbour for a while but in 1579 a storm moved so much shingle that the port was blocked and the fate of the town as a port was sealed.

In the 19th Century the movement of the beach was still causing a problem and William Catt the owner of the Tide Mills was concerned that this threatened his livelihood. In 1850 Catt acted by being one of several local men who sponsored a bold scheme to change the direction of the tide in the bay. It was hoped that a spit of land stretching out from Seaford Head would deflect westward travelling shingle into deeper waters of the bay and, where Canute had failed, it was thought that blowing up the cliff would succeed.

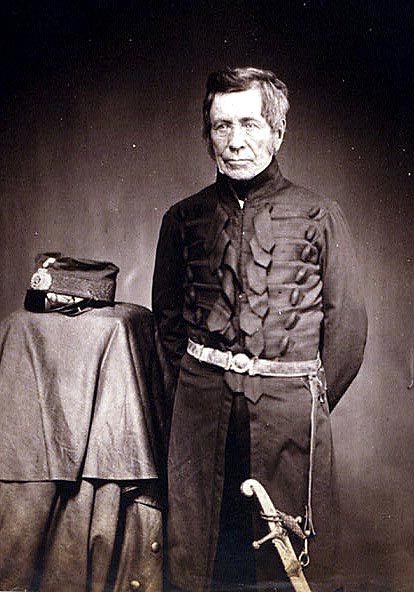

During the summer of 1850, the Board of Ordnance visited Seaford from their base in the Tower of London to survey the land and establish how the explosion could be effected. The Board of Ordnance was established in the 15th century and was responsible for designing, producing and supplying military stores and hardware. This organisation was also responsible for producing military maps (hence the Ordnance Survey of today) The whole operation was overseen by the Government Inspector of Fortifications who was Sir John Fox Burgoyne and I am sure that he stayed in Seaford whilst the operation was being planned.

Burgoyne was born in 1782, the illegitimate son of a famous General and an opera singer. He fought under Wellington in France and Spain during the Napoleonic Wars and later participated in the Wars of Independence in the USA. On returning to the UK Burgoyne was appointed a Major General and Inspector of Fortifications but prior to his work in Seaford he was involved in attempting to secure relief for the Irish who were starving due to the potato famine.

In July 1850 fifty-five men of the Royal Sappers and Miners arrived in Seaford and began to dig the galleries into Seaford Head where the powder would be stored. The Royal Sappers and Miners also had a long history and just six years later were to be re-organised as the “Royal Engineers” The men dug in from about of a third of the way up the face of the cliff and at seventy feet deep inside the cliff, two side galleries were dug. At the ends of these galleries were placed an explosive charge, each containing 12,000 pounds of powder. Three shafts were also dug into the cliff from the top. These were eighty-five feet from the cliff edge and each contained 600 pounds of powder.

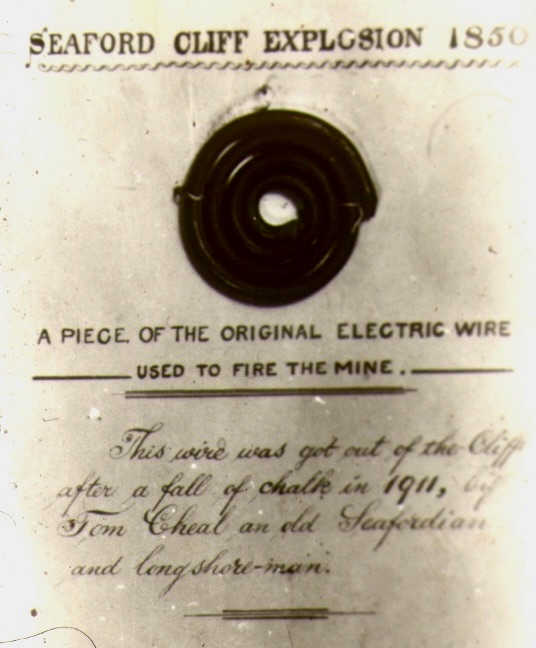

Detonator wires were led out from each cache of explosives and led to the cliff top where a small “battery-shed” had been built. The galleries and shafts were then back-filled or “tamped” to make the explosion more effective.

The explosive charges were due to be set at 3pm on Thursday 19th September 1850 and for days the town began to fill with visitors who expected to see one of the biggest spectacles ever witnessed in the south of England. The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway put on extra trains from London and surrounding towns and Directors of the railway company travelled to watch the event. The visitors included Lord Frederick Fitzclarence who was the illegitimate son of King William IV. The Military were represented by the 8th Duke of Beaufort who had been an Aide-de-Camp to Wellington and Lord George Paget who was later to participate in the Charge of the Light Brigade. It is even said that the great writer Charles Dickens, keen to see the great event, may well have stayed in the town the night before the big day when the Lodging Houses and Inns were full of visitors. I am sure this would have been a rowdy night – the sappers would have descended into the town, relieved that their work was over and would have mixed with the wide assortment of visitors. I am also sure that there was just one subject of conversation… “The Great Explosion”

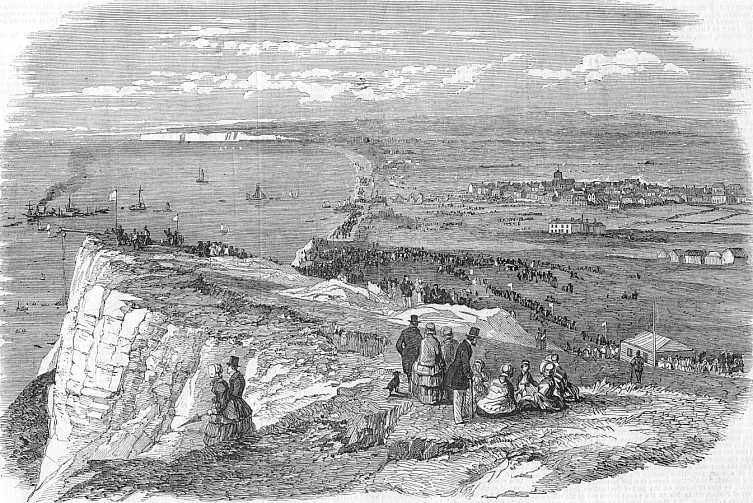

The morning of the Great Explosion was sunny and clear and the town was soon packed with visitors; by 10 ‘o’ clock the roads from the station were “lined with an immense concourse of persons” hundreds of which had arrived by train from London. The London Brighton and South Coast Railway ran trains every half an hour and a “monster train” from London was handsomely decorated with flags and flowers.

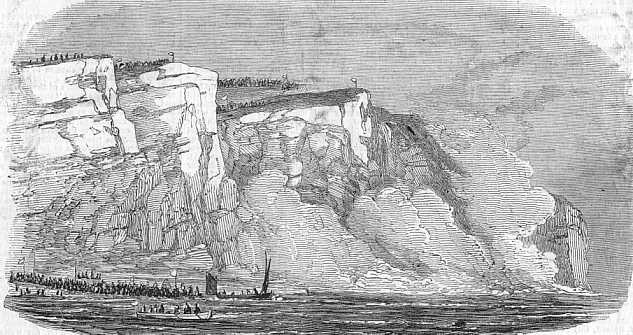

People travelled from all the nearby villages and towns and roads were blocked with “numerous carriages, gigs, flys and carts”. The pubs and restaurants of Seaford must have had a very profitable day although by 2pm most people were vying for position along the beach. Over 10,000 people packed the shoreline around Seaford Bay with thousands more on Seaford Head cliffs and even some in the water. Thousands also climbed the cliffs at Newhaven three miles away, but the richest visitors hired boats to view the event from the sea. Among these vessels was HMS Widgeon which was commanded by Captain Bullock and it is also rumoured that Charles Dickens managed to find a boat in which to view the spectacular event.

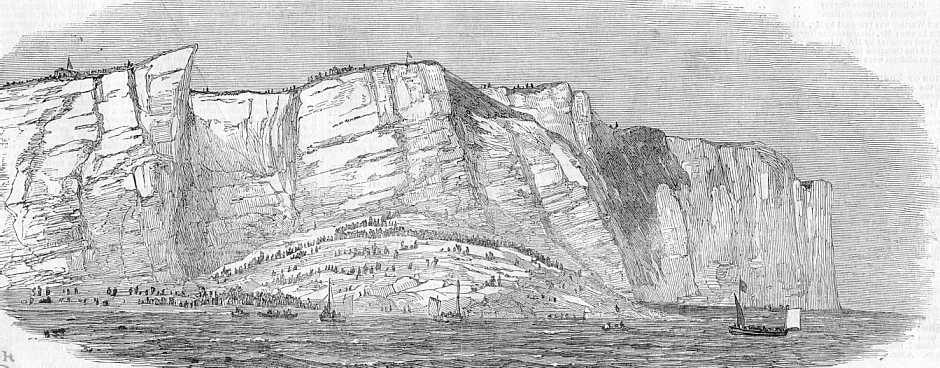

At three, the time that the explosion was due, all eyes turned to the Martello Tower where a flag was hoisted by Sir James Burgoyne, the military commander of the operation. A bugle sounded and this was answered by a bugle call by Sergeant Wright who was on duty at the Battery Shed which was on top of the cliffs and from where the detonations would be set. A few short moments of anticipation and silence was broken by the rumble and explosion of the lower two chambers and a massive wall of chalk bulged out at the base of the cliffs causing the cliffs above to fall. This probably cut the wires which connected the three smaller chambers of explosives which did not detonate. Seaford Head trembled, causing spectators to momentarily stagger and some spectators near the base of the cliff felt the force of the blast as similar to a mild electric shock. In Seaford, glasses on the tables of the Inns and houses rattled and there was some slight structural damage when a chimney dislodged some bricks. The explosion was even felt as far away as Newhaven.

The Sappers in the Battery Hut had a lucky escape when the cliff fell away within a few feet of the building, should the three other explosive chambers have detonated, they would have certainly have been killed. The explosion was followed by a huge cheer from the crowds who immediately began to swarm over the 50ft mound of chalk, the fact that there were three buried unexploded caches of explosive and the very real danger of further rock falls did not deter them – no “Health and Safety” concerns in those days! Indeed there were several minor chalk slips and several people were coated in a fine chalk dust giving them the appearance of flour millers!

The majority of people headed back to Seaford where the day had been declared a holiday. General Sir James Burgoyne had arranged for marquees to be erected at the town battery and here he entertained his men (officers and lower ranks) with a dinner.

For days afterwards crowds climbed over the chalk rubble, collecting fossils and even sections of the detonator wires. HMS Widgeon went directly from Seaford to Dover where Captain Bullock supervised the laying of the undersea telegraph to France.

The great Seaford Explosion was covered by the “Illustrated London News” which contained a detailed account and three engravings. (produced here) However, even this article, published just a week later, reported that much of the 380,000 tons of chalk which had been displaced was already beginning to get washed away by the strong tides.

The man-made breakwater caused by the explosion did not last the winter and twenty-five years later the great storm of 1875 prompted the Seaford Bay Company to invest in a sturdy sea-wall to protect the town. Following a rock-fall in 1911 evidence of the explosion was found following a rock fall…

No louder bang was to be heard in Seaford Bay until November 1944 when an ammunition barge exploded off Newhaven.

Fascinating story..I’d never heard of it.

LikeLike