Seaford Cemetery contains over 300 Commonwealth War Graves. Although they commemorate many local soldiers, most bear the Canadian maple-leaves. Nineteen graves however are carved with the crest of the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR). I have done extensive research and published details of the Canadian soldiers but this year I would like to tell the story of the West Indians buried at Seaford.

Early in the War men from the Caribbean travelled to England to enlist in the army and some were so keen that they stowed away on ships bound for England. In May 1915, nine men from Barbados appeared in Court in East London after they were found on board a steam-packet which had arrived the at nearby docks. The men were taken to an Army Recruiting Office and said that they had come to England to join the army but they were turned away because of their colour. The War Office was obviously not prepared for the support and enthusiasm offered by men from the West Indies. Private Griffiths of Trinidad (who trained at Seaford) said ‘Everything I know has been taught to me by the English and when I heard Lord Kitchener’s appeal for men I could not help but come.’

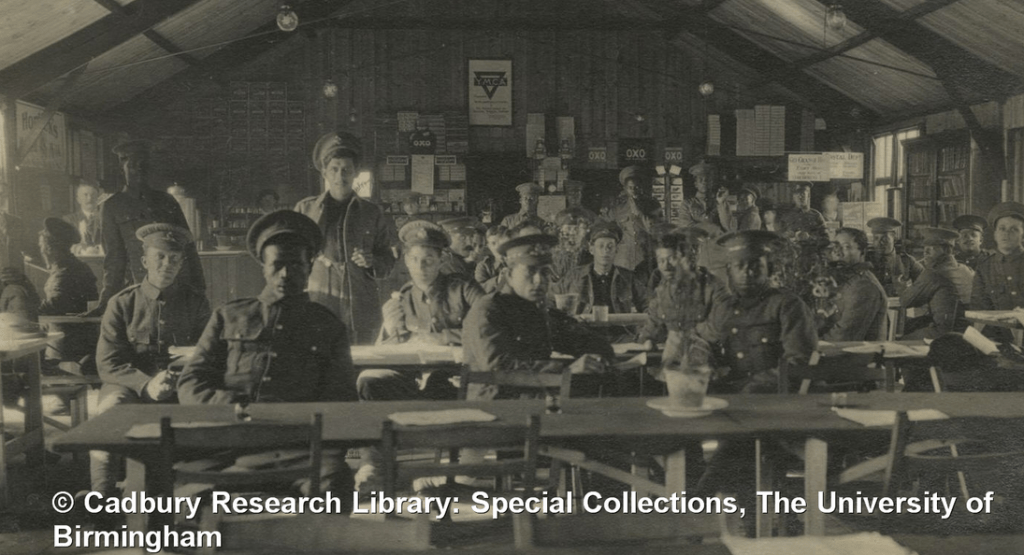

A West India Contingent Committee was established in London and their office became a place where West Indians arriving in London to join-up could get advice. It was decided that black volunteers should be sent to Seaford to await a decision on their recruitment and deployment. The first contingent of West Indians, mainly from Barbados and British Guiana, arrived in Seaford on 5 September 1915. A month later a ‘western port’ (probably Bristol) saw the arrival of 750 more men from the West Indies. On a frosty 4th October, they arrived at Seaford railway station and marched along Blatchington Road and up Blatchington Hill to Seaford’s North Camp.

On 20th October 1915, within a few days of the arrival one of the soldiers died. David Thomas Primo was a 35-year-old chemist from New Amsterdam, British Guyana, (now Guyana) South America. He was buried at Seaford Cemetery.

The British West Indies Regiment was established on 26th October and Army Order 4 of 1916 (passed 3 November 1915) conceded that the regiment should be recognised as a corps for the purposes of the Army Act. It is interesting that the regiment took a similar crest to that of the town in which it was raised.

During the Great War nearly 16,000 men served in the regiment, two thirds of these coming from Jamaica. It was apparent however the army was unsure of how to deal with these men and most of the officers and non-commissioned officers of the regiment were white men bought in from other regiments.

Shortly after arriving at the North Camp Seaford, Nathaniel Philips fell ill and died of natural causes on 9thNovember 1915. He was one of the first men to volunteer and had sailed from Trinidad on the transport ship Verdala. Records show his family were paid a ‘war-gratuity’ – £3 ! (About £400 today)

In November 1915 a group of black soldiers from the BWIR marched through London as part of the Lord Mayor’s Parade. The Daily News called them ‘huge and mighty men of valour.’

On 21st November 1915, Corporal James Lawrence Brown and two other West Indian soldiers, looking to explore the local countryside hired bicycles from William Allen, a ‘cycle agent’ in Broad Street, Seaford. He warned them to take care on the hills. The other soldiers were William Stuart and Cyril Gabriel all three men were from the island of St Vincent. They returned from Eastbourne after dark and ensured that their cycle lamps were lit, but on travelling down the hill towards Exceat Farm (now the Seven Sisters Visitor Centre) James Brown lost control and crashed into a tree. He died at the scene before a doctor (Lieutenant Walker of the Royal Army Medical Corps) could attend. He was taken to the Ravenscroft Hospital which was a converted school run by the Red Cross where his brother, who was also a member of the West Indian Regiment formally identified him. James Brown was buried at Seaford Cemetery. The subsequent inquest returned a verdict of accidental death. Sadly, one of the other cyclists, Cyril Gabriel was to die on active service and is buried at Jerusalem Cemetery in the Holy Land.

There are many reports of racism and discrimination toward black soldiers during the Great War however the Regiment’s stay in Seaford appears to have been accepted by the local people. In December 1915 the ‘Eastbourne Chronicle’ reported “At the outset, local people were inclined, not unnaturally, to be sceptical at the arrival of these strange soldiers of the King, and therefore the tribute of praise is all the more sincere when after a couple of month’s experience the residents generally speak in high terms of the behaviour of these men. Their presence is a striking tribute to the strength of the British Empire”

Local people had a nickname for the black soldiers – they were known as ‘Westies’

In December 1915 fifty-three West Indian soldiers, joined local people to be confirmed by the Bishop of Lewes and the ‘Eastbourne Chronicle’ reported “It was inspiring to see the reverent attitude of the soldiers, who being 4,000 miles from home, discharged their duty to the empire and found a welcome in the mother church”

31-year-old Charles Jarvis was the son of Kitty Lloyd and was born on 22nd March 1884 in Port Elizabeth on the small island of Bequia just to the south of Saint Vincent in the West Indies. I contacted the local newspaper on the Island and a relative of Charles, Rondolph Jarvis still lives on the island, managing a small cafe called ‘Moms’ which coincidentally is adjacent to the site of the house that Charles lived in (now a fruit and vegetable store) The cause of Charles death aged 31, is unknown but he is buried at Seaford Cemetery. It is nice to know that he is now being remembered both in Seaford and in Bequia on the centenary of his death.

Harold Constantine Grubb was born in Jamaica in 1897, the son of Samuel Lawrence and Zillah Celeste Grubb of Lethe which is a tiny hamlet about 5 miles south-west of Montego Bay, Jamaica. As a teenager, Harold was a member of the St James Company of the Jamaica Reserve Regiment. At the outbreak of the War he was one of the first men on the island to volunteer for military service abroad. Harold was a cheerful man, the Daily Gleaner of 28th December 1915 reported that he was “favourably known in the community and was a very quiet and well-behaved young man who was well thought of.” On Tuesday 6th July 1915 he attended Up-Park Military Training Camp, Kingston where he passed a medical examination and joined the Jamaica Contingent which crossed the Atlantic to England a few weeks later, eventually arriving at the North Camp, Seaford. On Sunday 12th December 1915, Harold went to Church in the morning, talking Holy Communion and afterwards went to Brighton. He returned to his army hut in good spirits and laughed with his friends before going to sleep. The next morning however he failed to respond to the reveille bugle all. His friend, Private W. Dunn, went to find out what was wrong and Harold complained that he had a severe pain in the back of his neck. Private Dunn reported the matter and Harold was taken immediately to the Camp Hospital, however he became breathless en-route. A chaplain was called to his bedside but Harold died as prayers were being said less than two hours after arriving at the hospital.

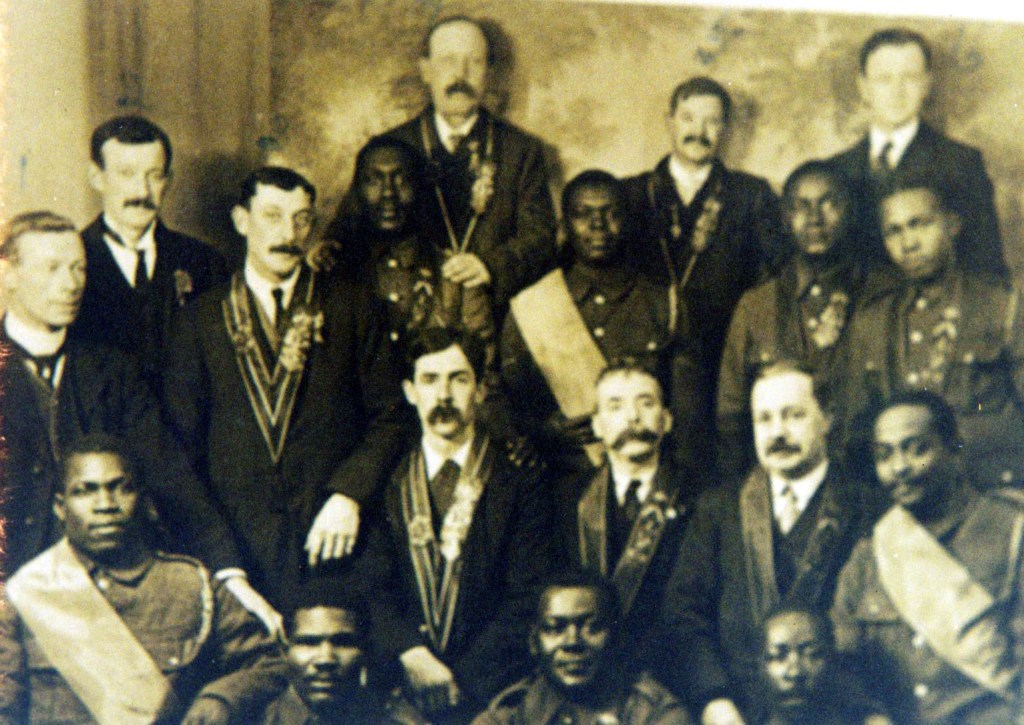

The Seaford Branch of the Ancient Order of Foresters soon discovered that some of the West Indian Soldiers were members of their organisation and they were invited to attend local meetings. A photograph shows these men looking relaxed in each other’s company. At the first meeting Private Clement from the “Pride of Hope’ Court of the Foresters in Trinidad said “We have left our homes and comforts because the call to arms is as much as it is to an Englishman. We are all British and are proud to be members of the Empire and we will shed our last drop of blood to uphold its integrity” His comments were met by applause.

The fact that the men were made welcome is also borne out in a letter sent by one of the soldiers, Private 875 Eric Hughes, to two sisters, Dorothy and Doris. He had obviously met the two girls before as he sends kind regards to their mother and then goes on to ask the two girls out to the pictures on Thursday night. Unfortunately it is not recorded if Eric got his date but it is interesting to see that he had the confidence to ask.

Nelson Fevrier was from the Caribbean island of St Lucia. He was the son of Alphonse and Brebin Fevrier of Micoud in the east side of the island. He joined the Army in September 1915 along with his cousin Dennis and both men came to Seaford to train at the North Camp. Sadly both men succumbed to fever and died. Both are buried at Seaford Cemetery.

Unlike the other members of the BWIR buried at Seaford, the relatives of Nelson have been traced and every year his great niece Timothea James, who now lives in South London, attends Seaford to lay flowers on his grave. She remembers playing with Nelson’s medals at her parent’s home in St Lucia but did not realise the significance of his sacrifice until 2006 when she first attended Seaford Cemetery.

Until 1918 the British West Indies Regiment was designated as a ‘Native Regiment‘ and the men were therefore paid less than white soldiers from other colonial troops such as those from South Africa, Canada and Australia. Initially the men of the British West Indies Regiment were not permitted to join their colleagues at the front line and were given labouring tasks and other auxiliary roles to perform. This must have been a crushing humiliation for these men who were just as able and willing as the rest of Kitchener’s Army.

Today it seems ironic that the British Army who were imprisoning conscientious objectors and executing deserters failed to utilise this huge band of willing volunteers.

The Regiment later saw active service in the Middle East fighting the Turks. Over 1,200 West Indian soldiers were killed or died during the war; many of these succumbed to pneumonia and mumps whilst in Seaford.

The nineteen men of the BWIR buried at Seaford were remembered by a poem by Valerie Bloom.

NINETEEN

We came for country and for glory, the light of battle in our eyes and courage that on those who are young or foolish recognise.

We’d been told that we were needed by the Motherland and we answered the Call-To-Arms, flimsy suitcase in our hand.

We arrived, eager to fight in some far off foreign shore and ill prepared for a mother’s embrace -bitter, cold and raw.

It was not for us the bugle’s summons, not for us the cannon’s roar or the endless treks through mud-fields, hungry, tired and footsore.

Not for us heart’s painful pounding, at drone of bombers overhead. Not for us sweet rest in Flanders poppies nodding round our bed.

And not for us the victor’s laurels, medals dangling from our breast. Not for us the decorations or commendations of conquest.

Even though we too have fallen, not in Ypres or Flanders Field, we like others gave our lives and, like them, refused to yield.

We came prepared to face the trenches, poison-gas and grenades, but not building, cleaning, freezing, shivering in an unheated Seaford hut.

Ambushed by the English winter, defeated by the stealth attack of mumps, pneumonia, influenza, we had no weapons to fight back.

Here a hundred years from home, a simple headstone tells our story. In the corner of this foreign field where we’re waiting still, for glory.

Although this poem remembers the nineteen members of the BWIR there are actually two other West-Indians buried at Seaford Cemetery; 20-year-old Aubrey Mitchell of St Vincent and 34-year-old Marcel Harford of Granada. Both were living in Canada at the start of war and are therefore buried under the maple-leaf of the Canadian Army.

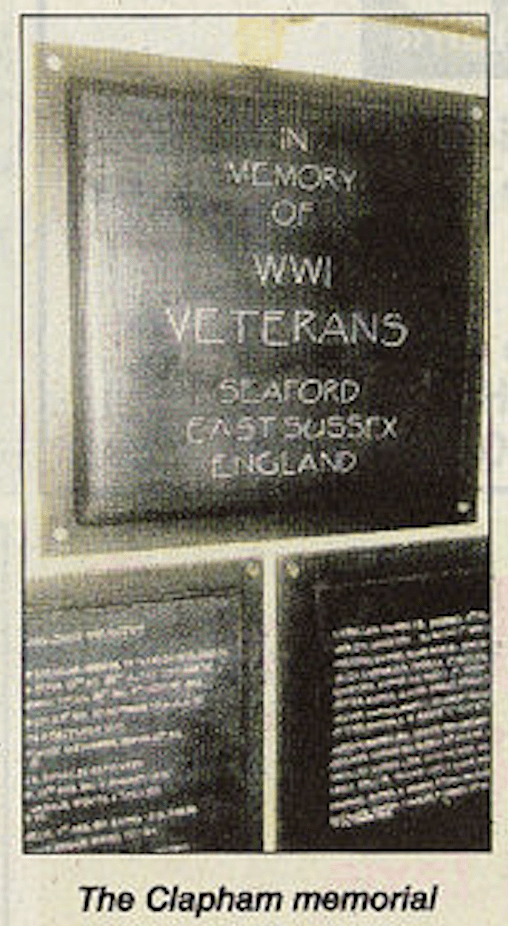

I am very pleased to have been able to research and make more people more aware of the role the West Indian Soldiers played in the Great War. In November 2006 I was honoured to be invited to the HQ of the West Indian Ex-Servicemen and Women’s Association in Clapham, South London to witness the unveiling of a memorial plaque to commemorate all the Commonwealth Soldiers buried at Seaford.

In November 2015 I was privileged to be involved in raising a blue plaque at Seaford Station to commemorate the West Indian Soldiers. I was asked to say a few words before the Mayor, Linda Wallraven unveiled it. Later on a similar plaque, sponsored by Harveys Brewery was unveiled at Seaford Cemetery.

In the late 1990s local historian, the late Pat Berry contacted the local branch of the Royal British Legion and suggested that a service be held at Seaford Cemetery to commemorate and remember the Commonwealth Soldiers buried there. This poignant service has been held every year since at 11am on the Tuesday following Remembrance Sunday. This year it will be held at 11am on Tuesday 12th November 2024. This is attended by members of the Royal British Legion, West Indian Ex- Servicemen and Women’s Association and other military organisations. You are welcome to attend.

Sources and thanks to:

Ancestry.com

Commonwealth War Graces Commission

West Indian Ex-Servicemen and Women’s Association.

Seaford Museum

The National Archives

Joy Lumsden of the Jamaican History Blog

Valerie Bloom www.valeriebloom.co.uk

The Nubian Jak Community Trust.

The Royal British Legion (Seaford Branch)