Document Ref: ACC10188/3/27 at the Keep Archive is listed as ‘Miscellaneous Printed matter collected by Captain James Ryder Mowatt.’ Mowatt (1755-1823) was the barrack-master at Eastbourne between 1797 and 1810. He was an experienced soldier have seen action with the Kings American Rangers during the American War of Independence.

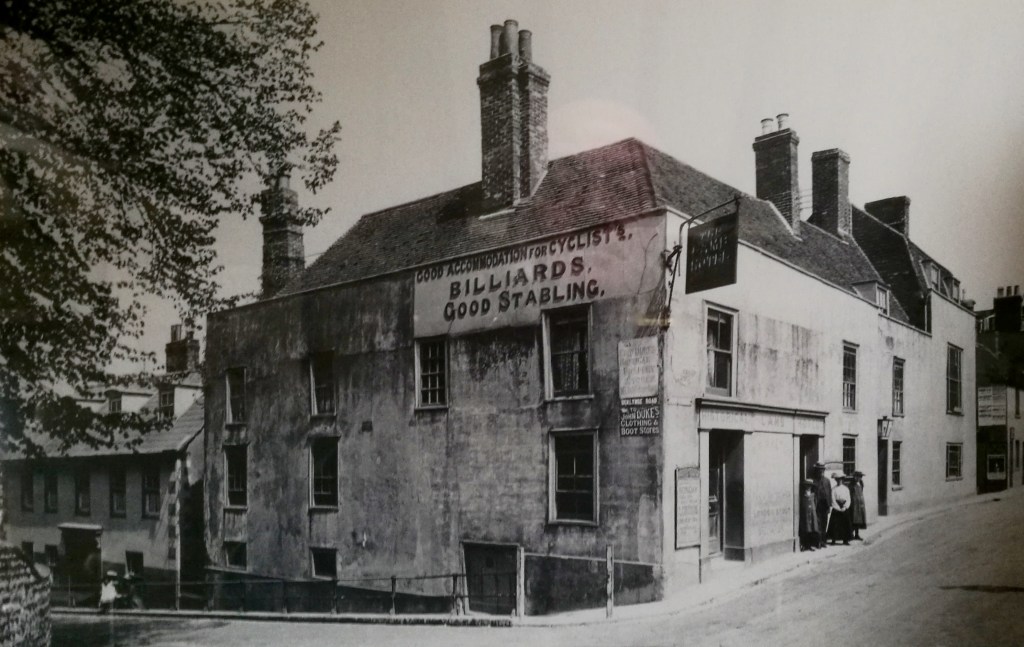

The Mowatt papers include a flyer for the appearance of “MR INGLEBY THE EMPEROR OF ALL CONJURORS” at the Lamb Inn, Eastbourne in 1810.

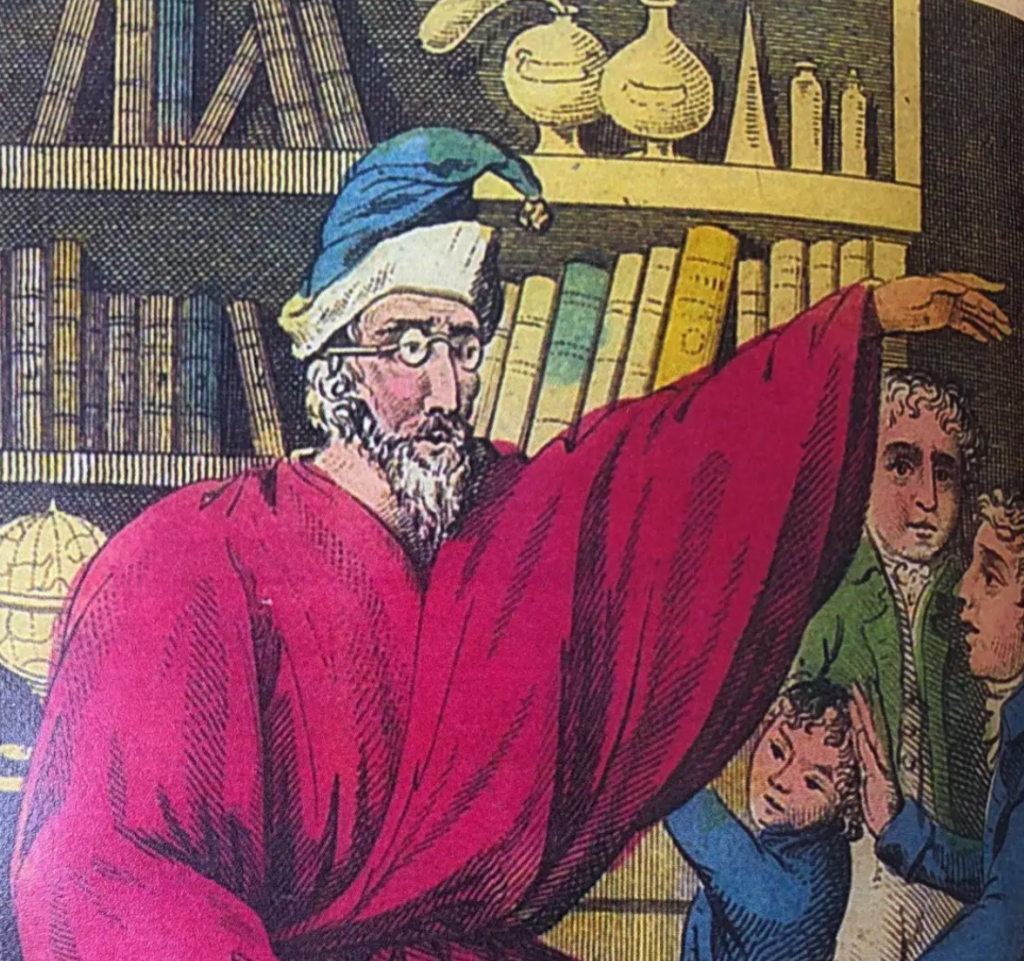

Mr. Ingleby was Thomas Ingleby. He was married to Christina who assisted him with his act by singing and dancing. They lived at 12, Craven Buildings, Drury Lane, London. Thomas first came to notice when he was engaged to perform at the Lyceum Theatre in late 1807. He performed every evening, the admission fee being between one shilling to four shillings. His act consisted of several magic tricks, the most spectacular being the revival of a chicken whose head he had chopped off. During breaks, the audience was entertained by Miss Young, a slack-wire performer. It is clear that his act was similar to that given in Eastbourne.

Ingleby was one of two famous London magicians, the other being a man by the name of Moritz who called himself ‘The King of All Conjurers’. After this, Ingleby described himself as ‘The Emperor of All Conjurers’ (see the heading for the Lamb poster).

In 1807 Moritz was performing in Cambridge. His show consisted of conjuring, a ‘learned dog’, a performing goldfinch and the summonsing of a phantasmagoria (a ghost). He was able to cook a pancake in his top hat and also had a female wire-walker called Belinda Price who performed under the name ‘Signora Belinda’. Moritz sacked Belinda after she hit him over the head with an umbrella (quite a feat considering she was only four feet tall!) but she was immediately hired by Thomas Ingleby. Moritz was furious that his star performer had gone to a rival and challenged Ingleby in the press where he wrote “I challenge any man in the world especially Ingleby, that lump of arrogance at the Lyceum for three hundred guineas to imitate my magical deceptions”

In 1808 Ingleby was modestly describing himself as ‘The Greatest Man in the World!’. He was available at this time to give private performances at the houses of nobility and the gentry for ten guineas. He challenged any other performer in the Kingdom to outperform his dexterity of hand for a wager of five hundred guineas. (about £25,000 today)

The following year Ingleby was at the height of his profession and engaged other magicians, a child musician, a whistling entertainer, a German rope-dancer and a ventriloquist, all accompanied by an orchestra. In 1810 another conjurer was engaged by the name of Signior Blue Beard. Performances were now at the Minor Theatre (formerly the Temple of Apollo) in Catherine Street, London.

Around this time Ingleby invited the celebrated painter Sarah Biffin (1784-1850) to his show. She was born without arms or legs and he probably wished to engage her as an act. He apparently offered to take her home after the performance but forgot and the poor woman was nearly locked in overnight.

Maybe Ingleby’s show was too costly and he had outstretched himself, as his theatre contract was terminated in April 1810. In the summer he was complaining in the press that other magicians were stealing his act. He then started to tour the country with a diminished act. In August he appeared at the Lamb Inn in Eastbourne.

Clearly Thomas Ingleby’s fortunes were waning and in 1815 he did what few magicians do – he gave the game away and published a book called ‘ Ingleby’s whole art of legerdemain, containing all the tricks and deceptions (never before published) as performed by the Emperor of Conjurors, at the Minor Theatre.’

This explained his famous act: “Two cocks, alike in plumage are used, one held in readiness but concealed from the spectators, while the other is placed upon the operating table on which its head is actually severed from the body. Then, while the head is being examined by the audience, the body is quickly removed and the living fowl substituted for it with its head concealed under its wing. As soon as the head is returned to the table, the conjurer passes it to an attendant, pronounces a few cabalistic words then slips the head of the living bird from under its wing upon which the cock struggles to its feet. If it is made to crow, the applause bestowed upon the operator is all the more enthusiastic. “

For the next few years Thomas appears in the press all over England and Scotland providing magical performances accompanied by Miss Young. The last advertised show seems to have been in Sheffield in December 1821 where his performance of reviving wildfowl was enhanced by him ‘swallowing two watches and half a dozen knives and forks’

Thomas Ingleby died in 1832 in Enniscorthy in Wexford, Ireland.

His widow, Christina remarried a man called Collins. On 15th June 1837 whilst travelling from Liverpool to London by canal (a slow but cheap form of travel), she was murdered and thrown into the canal in Staffordshire by four drunken bargemen who were subsequently executed. Ingleby was not around to revive them!

Sources:

The Keep (County Records Office, Brighton)

The Lives of Conjurers by Thomas Frost 1876.

National Newspaper Archives.