James Gorringe was the third and youngest son of James Gorringe of Upperton Farmhouse, Eastbourne. He was born in May 1866 in Eastbourne and educated at Brighton.

James married Alice Maria Spray (1864-1948) from Pevensey and they lived at ‘Kingsley’ 27, Devonshire Place, Eastbourne. They had two children Alfred Edward Kingsley Gorringe born 18th September 1894 and Alice Gwendoline Gorringe born 8th July 1899. I wonder if their son was named after their house or vice-versa?

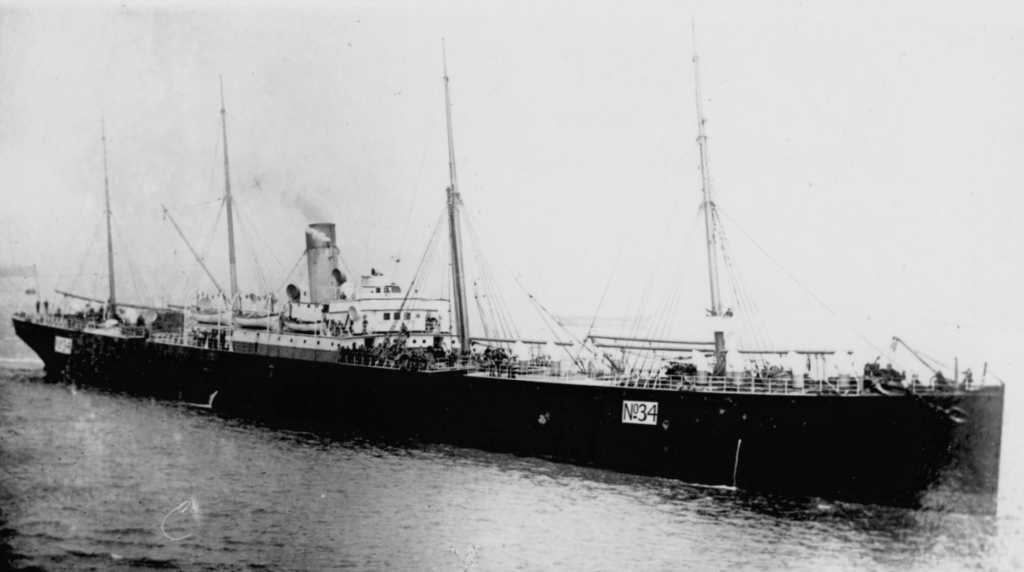

James had spent many years in the 14th King’s Hussars. (the nickname of which was the Emperor’s Chambermaids!) As an army reservist, James was liable to be called up for military service and this occurred in 1900 when he joined the At this time the Hussars were in action during the Second Boer War. This was a conflict aimed at removing Dutch-descended Boers from the mineral-rich South Africa. Heavily outnumbered by British troops, the Boers started a guerilla war. The British countered this by a ‘scorched earth’ policy of destroying Boer held farmsteads and imprisoning tens of thousands of civilians in Concentration Camps. This is the South Africa that James arrived in, onboard HM Transport Ship 34, a.k.a. SS Nomadic on Sunday 24thJune 1900.

James immediately wrote to his wife in Eastbourne from Cape Town “We arrived here this morning after a very good voyage with only three days of bad weather which I enjoyed as I do not get seasick”. The ship continued east around the coast to Durban. Again James found time to write to Alice. “Durban is a very nice, pretty place surrounded by trees and hills. I believe it is used as a sort of Eastbourne. I went out for a ride in a rickshaw which is a small carriage made for two and a man runs between the shafts. I enjoyed it very much. I have had a good quantity of fruit which is very cheap here (four bananas for a penny). I saw some Boer prisoners, Japs and Zulus. The Zulus do all the dock labouring and discharged our cargo singing and laughing all the time. There are hundreds of blacks in town with women carrying pitchers on their heads. Last night I went to the theatre and saw ‘The Gondoliers.’ “

The next part of the journey was by train inland to Queenstown (now Komani). Here James had breakfast with coffee made from the hot water of the steam engine. He described the countryside as ‘all khaki coloured’

It took two days for the train to get to Bloemfontein which James describes as “A decent built place crowded with soldiers and hospitals but they have been burying the dead (between 20 and 30 a day) from dysentery and enteric”. During the Boer War, more men died of disease than in action and James was clearly aware of the dangers, saying “I do not drink much water and what I do I filter. I am careful to ask about the source of the water before filling my bottle”

James continued his journey north-eastwards by road, complaining that the nights were bitterly cold and the army had not provided blankets. He arrived at Kroonstad (now Maokeng) to join the rest of his regiment on 6thJuly 1900.

He next writes to his wife on 1st August from Middleburg where he has been left by his regiment with a detachment of 60 men. By this time he had seen fighting, although from a distance, reporting that the Boers fired ‘pom-poms’ (large shells filled with bullets that scatter in all directions) but these fell short of the British positions and there were no casualties. He tells Alice “Life out here is really rough. You feel tired after a full day on patrol and have to cook your own dinner, so before getting back to camp you have to find wood, so we take posts or wood from deserted houses.” A suburb of Middleburg is still called ‘Kanonkop’ literally ‘Cannon Hill’ which is probably where James was based. Later a large concentration camp was built nearby.

James moved east, close to the border of Swaziland (now Eswatini). It is now September 1900 and James writes home to say that he was one of the first to ride into to the newly taken town of Barberton. “I have been in a good many fights since I last wrote but thanks to God I have come out without a scratch. There has been some very nasty fighting but the Boers have now all left the town. Everyone is tired of this rough life”

His last letter is dated 11th October and was written in Machado Dorp (now eNtokozweni). He is clearly tired. “The miles of veldt we travel; the trouble with the horses, the mules and the cattle; the cold nights out in the open with only your cloak and a blanket; the sentry duty, the getting of wood to boil your little cup of coffee; trying to fry your meat with no fat; the hot sun and the thirst – it is all most trying” But he hoped that his ordeal was soon to be over “It seems like a dream but are now on our way home. If we do not meet the enemy, I may be home by Christmas. How I am longing to see you and the children again. Remember me to all my friends”

Sadly, James did meet the enemy – not the Boers, but the deadlier foe of enteric disease. On 5th November he was admitted to the Model School Hospital, Pretoria. His last letter is dated 10th November 1900. “We marched into Pretoria through fearful rains which lasted day and night. I dismounted wet through and began to feel the cold strike me. The doctor admitted me to hospital where I am now very comfortable and well looked after. I have port-wine and plenty of nourishment”

James died aged 37 years on 14th December 1900. The news of his death was received at home in Eastbourne by Christmas. A Memorial Service was held at Holy Trinity Church 30th December and a few weeks later a brass memorial was fixed to the south aisle of St Mary’s Church where it can still be seen today.

Sources: National Newspaper Archives and http://www.angloboerwar.com