The graveyard attached to St John Sub-Castro (under the castle) Church in Lewes is full of interesting gravestones. Yesterday I visited the sloping grounds with two old schoolfriends and pointed out some graves of interest. Many years ago, when we lived in Lewes, my wife and I ‘adopted’ three graves to look after, but much of the burial ground was then jungle-like and access to many of the graves was impossible. I was pleased to see that in recent years nature had been tamed to make the graveyard a far more pleasant place to visit, however some areas have been left for wildlife. Well done to all concerned. I pointed out the graves of some notable people; Mark Sharp whose carpentry tools grace his gravestone, John Every the ironmaster and the Crimean Memorial which lists the Scandinavian soldiers who died in the nearby Naval Prison.

One grave was rather overgrown but is the last resting place of Charles Dawson, a Sussex Solicitor who was the clerk to the Uckfield Magistrates and to Uckfield Urban District Council.

He lived with his wife Helene at Castle Lodge, alongside the imposing castle. (incidentally his home was once my doctor’s surgery) In his spare time (of which he seemed to have a lot) he was also an amateur historian or ‘antiquarian’ as they were then known.

Charles was noted for examining the Bayeux Tapestry, excavating tunnels under Hastings Castle and discovering natural gas at Heathfield. He discovered a Roman statue and a prehistoric axe near Bexhill and even once found a toad in a nodule of flint (now on display at Brighton Museum).

Today however, he is remembered as the man who ‘discovered’ the ‘Piltdown Man’.

On 18th December 1912 the Brighton Argus reported that the palaeolithic human skull and mandible found at Piltdown had gone on display at the Geological Society in London where the finder, Mr Charles Dawson had read a paper on its discovery. He told the audience that a few years earlier in 1908, he had been walking on Piltdown Common near Fletching when he saw some labourers digging out gravel for farm roads. One of the men gave him a piece of human skull which he said had been found nearby. Dawson had returned to the spot in November 1911 when luckily (very luckily) he had managed to retrieve more pieces of the same skull. In the spring of 1912 he had returned to the same spot and retrieved half of the lower jaw of the skull.

He had taken the specimens to Dr Arthur Smith Woodward (1864-1944) of the Natural History Museum who had realised that the pieces were the skull of a female representing a ‘hitherto unknown species of homo’. Dr Woodward (who lived at Haywards Heath) proposed that the new species be called ‘Homo Dawsoni’ after its finder. Despite the good doctor believing the skull was that of a female the skull soon became known as ‘The Piltdown Man’.

The skull appeared similar to that of primitive ‘Heidelberg Man’ although the jaw seemed to be more ape-like resembling a chimpanzee. It appeared that what had been uncovered and discovered in a Sussex gravel-pit was none other than ‘The Missing Link’ – the actual proof that Charles Darwen had been right and man had descended from apes.

Dr Woodward told the press “Many hundreds and thousands of years ago, a strange hairy, ape-like creature, a female member of a curious race, from whom all other animals shrank, roamed the dark forests of Sussex. She was a new type, possessing a new cunning, and an amazing power over the other denizens of the forest, for she could do what they could not – use implements and clothe herself in skins. She was the ancestress of the English race of today!” (Clearly the sensitivities of the time required any woman, however ancient to be clothed!)

In 1912 the Brighton Press reported that a ‘Folk Museum’ was due to open at the Public Library. The Brighton Gazette was sceptical “Imagine exhibits showing the shaggy old peasants of West Sussex who could neither read or write and who tenaciously believed that potato blight was ‘work of the papacy’ or the grimy East Sussex charcoal burners!” However what could be displayed, was the “Piltdown Man who is destined to make history”

The exhibit was far too important to be on display in Sussex – by May 1913 the ‘wonderful skull’ was “The most interesting exhibit at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington.” In August 1913 members of the medical Congress, who were meeting in London, visited the exhibit and declared that it was 500,000 years old. Other eminent men had dated the remains to the Pleistocene period, potentially making the remains 5 million years old. Charles Dawson of course was just the finder of the skull and was happy to be feted and gave many lectures which no doubt made him lots of money. He had been elected as a Fellow of the Geological Society and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1895, despite not having a degree, which was in those days remarkable. The British Museum named him as an ‘Honorary Collector’. The press dubbed him ‘The Sussex Wizzard’.

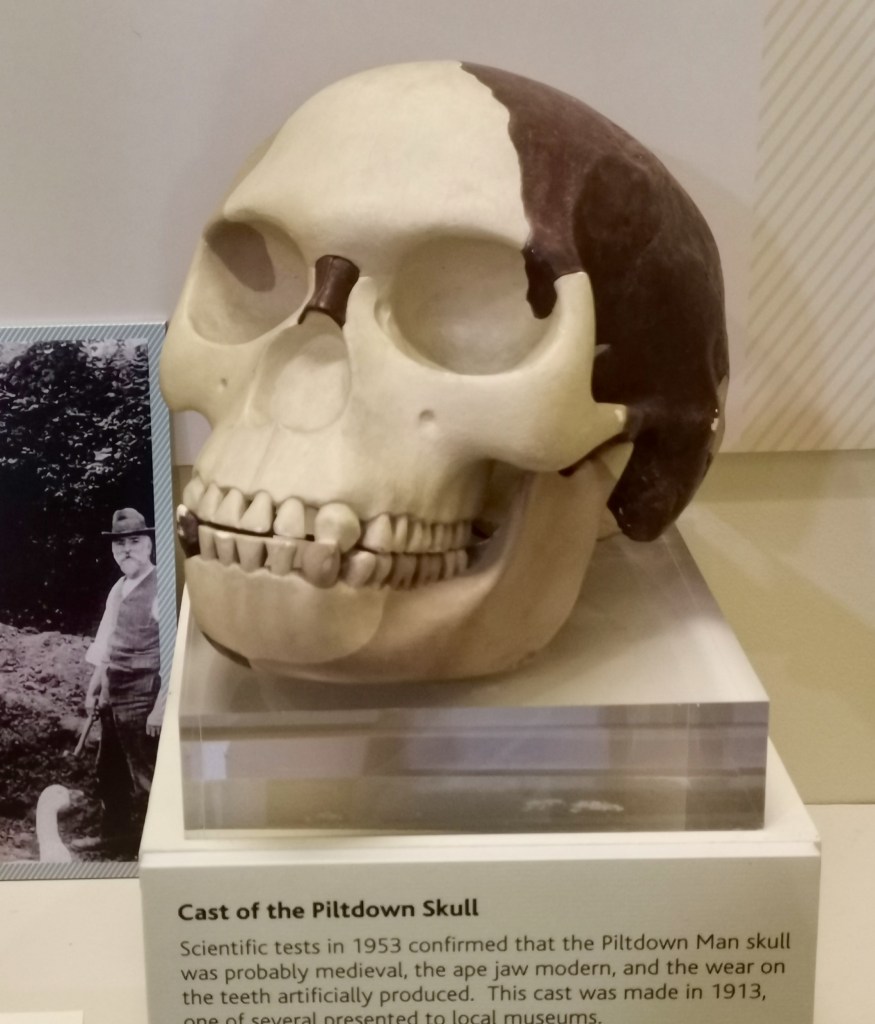

Reconstructions of the whole skull were made leading to even more debate (what size brain did they have – could they talk – what did they eat?) One of these reconstructions was given to Hastings Museum where it can still be seen today. (Dawson was the co-founder of the Hastings and St Leonards Museum Association)

But was the skull all that it seemed? Mr W.J. Lewis-Abbott, a fellow of the Geological Society was an early sceptic. Writing that same month (Daily Express 23rd August 1913), he asked – Were not the gravel-beds, where Piltdown Man was found, far too old geologically for human remains to be found, and wasn’t much of the Sussex Weald under water or ice at that time? Not really the ideal conditions for early Sussex Man. He asked “Why has the new chimpanzoid jaw produced such a new sensation?” Despite further excavations no further archaeological evidence was found at Piltdown. It is also interesting that the discovery of the ‘Piltdown Man’ was not mentioned in the ‘Sussex Archaeological Collections’.

Dawson no doubt did some excellent research, writing about the history of Pevensey Castle (although stamped Roman bricks he found were dubious) and the Battle of Beachy Head (although his finding of two wrecked Dutch ships in Pevensey Bay seems unlikely)

Charles died of pernicious anaemia aged 52 years at Castle Lodge on 10th August 1916. He was buried two days later at St John Sub Castro Church, the grave was lined with evergreens and the local Freemasons, of which he was a member, dropped sprigs of acacia (a masonic symbol of immortality) into the open grave. The funeral was conducted by the Reverend Leyland Dawson, his brother.

Within a few years, academics were starting to cast doubt on the ‘finds’ that Charles had made, many of them seemed too good to be true. He claimed to have made many ancient finds in the ‘Lavant Caves’ near Chichester but the only evidence was what he had written to the press. An ancient horseshoe found at Uckfield was found to be relatively modern but artificially ‘aged’.

In 1953 Time Magazine published a report proving that the Piltdown skull was a forgery being an amalgam of a medieval human skull and ancient chimpanzee and orangutan bones artificially stained to give an appearance of great age. The teeth had also clearly been filed. The Piltdown Man was a man that never existed.

On 23rd July 1938, the anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith had unveiled a memorial at Piltdown marking the exact spot where the ‘Piltdown Man’ was discovered. In his speech, Sir Arthur said “The name of Charles Dawson is certain of remembrance”. That has become true but maybe for the wrong reasons.

Yesterday, I stood with my friends beside his grave at Lewes and listened – but no, we couldn’t hear him turning in it!

Sources:

Internet research particularly the National Newspaper Archives

Sussex Archaeological Collections particularly Volume 151