This story has it all – rioting, nuns, a funeral and a Christmas carol – and it’s all based in Sussex!

I suppose the story starts with Edward Bouverie Pusey (1880-1882). He was a theologian who, along with John Henry Newman (later Cardinal Newman) (1801-1890), was one of the founders of the ‘Oxford Movement’. This group of High-Church academics, based at Oxford University, sought to bring the Church of England closer to the Catholic Church. A number of tracts were published, the most controversial being ‘Tract 90’ which sought prove that the Church of England was a Catholic rather than a Protestant church.

John Mason Neale was born in London in 1818, and although he studied theology at Cambridge, was heavily influenced by the Oxford Movement. In 1840 he was appointed the Chaplain of Downing College, Cambridge and became interested in church architecture, so much so that he founded the Cambridge Camden Society which advocated a Gothic revival which included a return to religious decoration in churches and also the restoration of some Catholic rituals.

Neale was ordained in May 1842 and became the Vicar of Crawley, but not for long; his ‘delicate constitution’ required a long break on the Island of Maderia where he spent his time translating Eastern hymns and religious books into English. He could apparently speak twenty languages and of his more noted translations, were poems written by Saint Bernard of Morlaix (Brittany), who was a Cluniac monk. Cluny was a Benedictine monastery in France which, in the Middle Ages, had several outposts in England, one of them being Lewes Priory. A few months later, he returned to Sussex refreshed.

Back in England Neale settled in Sussex, initially at Rotherfield but in he was appointed as the Warden and Chaplain to Sackville College Alms-houses at East Grinstead.

It was here that he established an order of nuns called ‘The Society of Saint Margaret’ also known as ‘The Sisters of Mercy’. Anglican nuns were rare, but not unknown – you will know this if you have watched ‘Call the Midwife’. Neale’s Catholic leanings came to the attention of the Bishop of Chichester, who received 19 complaints about his conduct which interestingly included ‘the mode in which he conducted funerals’. The Bishop ‘inhibited’ him – banning him from preaching in the diocese. This was probably a wise move by the Bishop as at this time East Sussex was a hotbed of Protestant fervour.

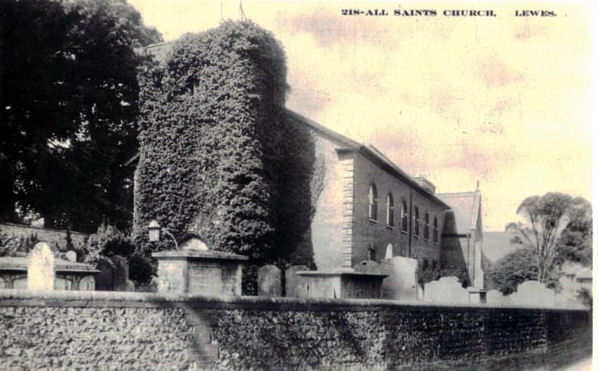

One of the Sisters of Mercy was 30-year-old, Emily Scobell, the daughter of the Reverend John Scobell, the vicar of All Saints Church at Lewes, the county town of Sussex. Emily moved to East Grinstead to become a nun with the Society of St Margaret but after a few years contracted scarlet fever, dying on Friday 13thNovember 1857. Emily had written a will leaving her money (a bequest from her grandfather) to her father and also she wished to be buried in the family vault at All Saints, Lewes next to her mother Eliza who had died a couple of years earlier.

When the Reverend Scobell contacted East Grinstead to arrange his daughters funeral, he was surprised and probably angry and incredulous be told that Emily had recanted her will on her deathbed and now wished to leave her money to the Sisters of Mercy. The Reverend John Mason Neale also told the grieving father that he wished to conduct the funeral himself in Lewes and if he refused, he would bury the girl in East Grinstead.

The funeral was arranged for Wednesday 18th November 1857. Emily’s coffin arrived by train at Lewes Station at 5.18pm for a 6pm funeral. This seems to be an odd time considering it would have been dark.

The Reverend Neale and the Sisters of Mercy had arranged the cortege (funeral procession) which was remarkably different to the norms of the time; rather than the coffin having a flat top, it was domed ‘something like the roof of a building’ and the bier was ‘a handcart with roofed lattice work around the coffin’. Maybe the most contentious item was the pall, the cloth that covers the coffin; rather than being black felt, it was white cashmere with a black cross in the centre with smaller crosses around the edge.

To many eyes, the cortege was ‘papish’ and, according to the Sussex Advertiser, designed ‘to excite an adverse feeling in the minds of spectators due to its unusual appearance’. It did! It must be remembered that Lewes at the time was a firm stronghold of Protestantism and had been since the burning of Protestant Martyrs during Queen Mary’s persecutions. Every year the people of Lewes held anti-Catholic bonfire parades on 5thNovember – just a few days before the funeral and still fresh in people’s minds. Neale was clearly using the poor girls funeral to make a statement.

Neale and eight of his nuns took a position at the head of the procession. There was obviously friction when the bereaved father, his daughter and two sons arrived as Neale and the nuns initially refused to yield. By this time the word had quickly spread that something was going on and a large crowd lined the streets between the station and the short distance to All Saints Church. When the coffin was brought into the church, the nuns arranged themselves around it and Neale clearly expected to take the service. To me it was remarkably insensitive for Neale to try to usurp the wishes of a grieving father in his own church! In the end the service was conducted by the Reverend Hutchinson, the Canon of Chichester Cathedral who presumably outranked both men.

The internment was to be held in the family vault, which can still be seen to the north of the churchyard at All Saints. By now a large crowd had arrived at the churchyard and resulted in the local constabulary sending Sergeant Baldwin and PC Nelson Putland to stand by to prevent any disturbance.

Emily’s coffin was carried to the family vault accompanied by the grieving family, much to the annoyance of the Reverend Neale, who clearly wished to add a supplement to the funeral service. The door to the vault was quickly locked and despite trying, Neale could not get in, indeed he was prevented by the crowd from getting near the vault. The grieving family left the scene, but Neale remained and loudly demanded that the police give him access to the vault. PC Putland told the frustrated clergyman that this was a matter beyond his duty and advised him to leave the churchyard for his own safety. By now the crowd were getting restless and there were cries of “No Popery” and “Turn him out!” . Neale told the constable that he would not leave and if the police would not allow him access to the coffin, he would break into the vault that night. By now the crowd were yelling “Down with the Pope” and other bonfire inspired chants. Neale was very lucky not to be arrested but the crowd took the matter into their own hands and ‘hustled him from the churchyard’. During this process Neale and several of the nuns were pushed to the ground.

By now a crowd of several hundred had arrived as had four other constables. The police implored Neale and the nuns to take refuge in a nearby building but he refused. The Sussex Advertiser said that Neale’s behaviour was incomprehensible and reprehensible and that he seemed to revel in the thought of a martyrs fate.

The mob pushed Neale and four of the nuns back towards the railway station (four of the nuns having taken refuge in a schoolroom in Lansdown Place.) They were forced along the street where they eventually sought refuge in the Kings Head pub. The mob (now described as a disorderly rabble) took siege but Neale did something else rather unwise – he put money behind the bar to buy beer for the mob outside! (If there is one thing worse than a rioter it is a drunken rioter.)

Police reinforcements arrived in the form of Superintendent Jenner, Inspector Daws and twelve other constables, no doubt being called in for emergency duty. The superintendent negotiated with the crowd asking for the nuns to be allowed to return to the station. The crowd shouted “We don’t want to hurt them – we want the Pope inside!”. Whilst the sisters were allowed out of the front of the pub, Neale escaped through a back door, scaling several garden walls to return to the station. Peace eventually returned to Lewes – but only for 24 hours. The next day the Reverend John Mason Neale returned !

He arrived at Lewes with the Lady Superior of the Sisters of Mercy at 4.35pm. (again why leave it so late in the day when it was dark?) First he went to see the Reverend Scobell, Eliza’s father, to ask for access to her coffin. Scobell refused. Next Neale visited the Parish Clerk and then the church sexton insisting that he be given keys to the vault – again his demands were refused.

By this time news had got around that Neale and a companion had returned to Lewes and again a large mob appeared which jostled their carriage causing them to seek refuge in the White Hart Inn in the High Street. Soon about 300 people were outside and so were the police, armed with Mr Dalbaic, a local magistrate ready to read the riot act if necessary.

Superintendent Jenner was clearly annoyed by Neale’s behaviour and remonstrated with him for returning to Lewes without giving him notice. Neale told the police officer that he “did not know he was coming but had business with an ironmonger’. This was either a lie or it indicated that Neale had intended to break into the vault by force against the wishes of the grieving family – a clear act of criminal damage.

The superintendent told the recalcitrant vicar to leave town (and probably not to come back!) and Neale and the Mother Superior were bundled into a carriage to take them down to the railway station but as they left there was a volley of stones and the windows of the vehicle were smashed out.

At the railway station there was another large mob and again stones were thrown. Neale, seeming to like the negative attention refused to go into a waiting room for safety but stood on the platform surrounded by about fifty hissing and booing Lewesians. When the train arrived Neale and the Mother Superior entered the carriage but, rather than take his seat, Neale stood, arms crossed at the open window grinning at his detractors. Superintendent Jenner again implored Neale to stop ‘winding-up’ the crowd and to close the train window and to take his seat but he refused. The Sussex Advertiser said he ‘pertinaciously protruded from the window in an unseemly and defiant bearing’. As the train left, several stones were thrown at the train, one appearing to hit the truculent clergyman on the forehead.

The following day, the Friday, extra police monitored hundreds of local people who roamed the streets looking for Neale who was rumoured to have returned to Lewes but he hadn’t. That same day a Charles Rooke appeared at the Magistrates Court where Inspector Anscombe of the Railway Police gave evidence that Rooke had been one of the stone-throwers at the station. Rooke was bound over to keep the peace.

Back in East Grinstead, Neale wrote a long letter which was printed in the Times giving his own version of events calling the people of Lewes ‘A mob only too notorious in the annals of lawlessness.’

A few weeks later he published a long tract “THE LEWES RIOT – ITS CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES – A LETTER TO THE LORD BISHOP OF CHICHESTER BY THE REV. J M. NEALE M.A.” In this he appears to show that Emily Scobell was a victim of an overbearing father. “She was rendered miserable at home by the unkindness of her father, forbidden to seek any council or comfort but from a parent who was wrong-doing her”. Despite the title of the publication he does not mention the ‘barbarous riot’ in the churchyard until page 33 of the 35 page document. He denied trying to enter the funeral vault and any wrongdoing.

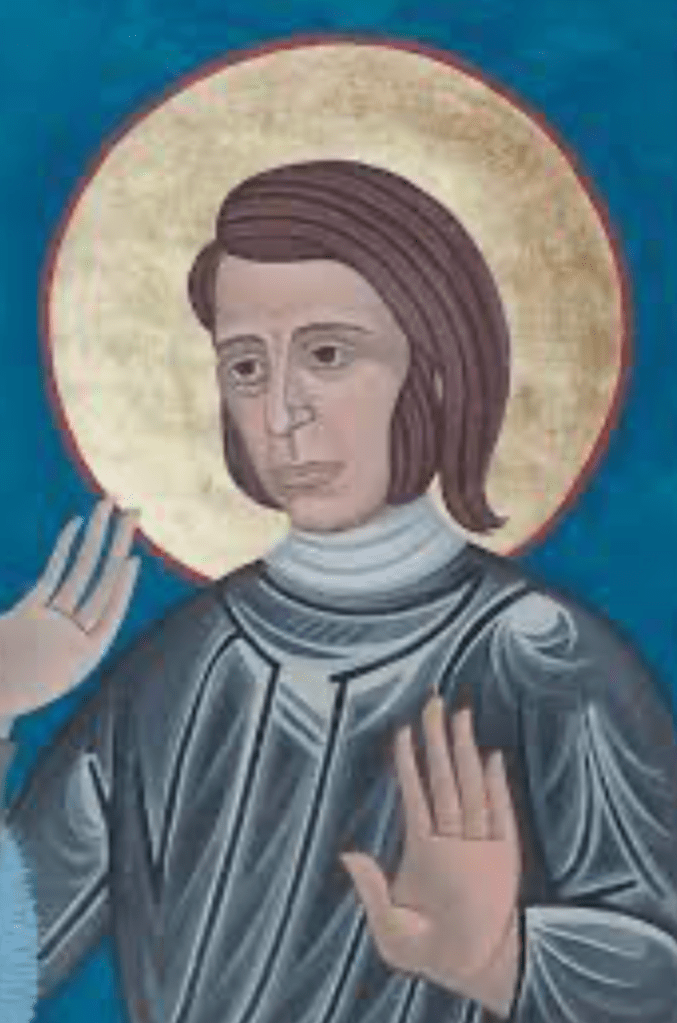

The Lewes Riots were soon forgotton and back in East Grinstead the Reverend Neale settled down to what he did best and obviously enjoyed, translating and writing hymns. He is credited with saving, translating and reviving hundreds of ancient hymns from around the world. He translated the popular ‘O come O Come Emmanuel.’ He translated and made popular the German carol ‘In Dulci Jubilo’ as ‘Good Christian Men Rejoyce’ (Mike Oldfield got to number 4 in the 1975 Christmas charts with it). But perhaps his best known work is the Christmas Carol ‘Good King Wenceslas’, known and loved around the globe.

John Mason Neale died in East Grinstead in 1866. Forty years after his death in 1906 a biography was written. A very one-sided account of the Lewes riots is given, blaming them on the bereaved father, Reverend Scobell calling him ‘unrestrained, violent and vindictive’.

Today Neale is revered as a saint by the Anglican Communion (His feast day is 7th August). On 24th July 1966 the Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, attended his grave at East Grinstead to unveil a plaque which describes Neale as a Liturgiologist, Ecclesiologist, Church Historian, Author and Translator of Hymns. He was certainly a great man but maybe his behaviour at Lewes shows a different side to him.

It is fair to say that as an ex police officer, I am biased and look at the riots from a public-order rather than a religious perspective. We can never know what went on beforehand between the Reverend Neale, the Reverend Scobell and his daughter Emily. Neale said that he had never tried to gain access to the locked vault. If he was telling the truth, the local vicar, parish clerk, church sexton, local reporter and the police were all telling lies, which I personally think is unlikely.

Neale was ‘High-Church’ with clear Catholic leanings and had already come to notice for the mode in which he conducted funerals. He was fool-hardy or arrogant if he thought that he could conduct a ‘Catholic style’ funeral in highly Protestant Lewes so soon after Bonfire Night without any repercussions.

There are other questions to be asked about the riots; how did the ‘mob’ know about the funeral and why was it at an unusually late hour? Had the Reverend Scobell arranged the funeral knowing that many Lewesian Bonfire Boys would be available after working hours and had he pre-warned them?

I tend to believe the police reports of Neale’s confrontational behaviour at the graveyard and the railway station. It appears that he could have avoided much of the trouble if he had taken police advice and ‘retired from the scene’ and was lucky to not be arrested. I have taken much of the account from newspaper articles of the time. Maybe local reporters were biased towards the local family (and the local mob!). I suppose we will never know the full story but when you next hear Good King Wenceslas think of the Reverend Neale and his interesting past.

Sources:

Contemporary Newspapers particularly Sussex Advertiser 24th November 1857

John Mason Neale – A Memoir. E.A. Towle 1906

Lewes – Its Religious History. J.M. Connell 1931

Wikipedia and Internet research

Great article, Kevin! Did not know about this so very informative.

LikeLike